“Please Allow This Music to Flow Into You”: Daniel Schmidt, Mills College, and the History of American Gamelan

American gamelan composer Daniel Schmidt said of his third album, Cloud Shadows, “Starting at perhaps age four or five, I would sit on the top step of our front porch, just under the overhang of the roof, and look at the rain. I was transported. I remember quite clearly the transcendent state I would enter. But I learned early to keep my experiences with the rain to myself. At church I would hear references to the ‘spiritual.’ It seemed to be defined as something beyond everyday life, and that puzzled me, because it sounded much like my own experience when watching rain. I ask you, as you listen to this album, to imagine the rain as I felt it as a child. Please allow this music to flow into you.”

What is it about gamelan music that touches composers, performers, and listeners so deeply? For many, gamelan music connects to elements of spirituality, to peacefulness and contentment. Gamelan music did not come to the United States through a diaspora, yet occupies a fascinating space within American culture. Gamelan is a musical ensemble that originates from various areas of Indonesia, most notably Java and Bali, is one of the most popular “world music” (a woefully out-of-date, but unfortunately still often used term) ensembles in American universities, and likewise a staple of “world music” bins at record stores. Since the early twentieth century, gamelan music has played a crucial role in the compositions of many American New Music composers, to the point that American gamelan music came to be recognized as its own subset of gamelan music. The history of how gamelan came to be so culturally significant in the United States is complex, a combination of the echoes of colonialist history, freedoms and limitations within American college music education, and genuine curiosity and admiration for gorgeous, intricate musical experiences.

Photograph by Tara Sosrowardoyo, from Jennifer Lindsay, Javanese Gamelan: Traditional Orchestra of Indonesia (1992)

We recently got in two CDs from the label Recital, who put out the first albums of American gamelan music composer Daniel Schmidt. This week’s blog explores the history of how American gamelan developed and looks at the history of Mills College as an epicenter for American New Music and Daniel Schmidt’s compositions. This is a dense topic, the subject of books and dissertations. I will cover this material as concisely as possible, but I also encourage you to check out the books and articles I referenced to learn even more. Also, for the purposes of this post, I focus especially on Javanese gamelan.

Gamelans are typically composed of instruments such as metallophones (i.e. xylophones), gongs, gong-chimes, flutes, cymbals, a bowed instrument called a rebab, oboes, drums (kendhang/Kendang), and solo and choral voices. Javanese gamelan dates back to the eighth century courts of the Mataram kingdom, alongside other courtly arts such as poetry, dance, and shadow puppet theatre (wayang kulit). Javanese mythology tells of how the god Sang Hyang Guru invented the gong to signal the other gods, and then created two other gongs to send more complex signals, which makes up the gong set of gamelan. Two styles of gamelan playing developed over the course of time, each with different sets of instruments: a loud instrumental style and a soft style which resembled the cadence of Javanese poetry. Today, gamelan is an integral part of ceremonies, rituals, concerts, festivals, dance, and theatre.

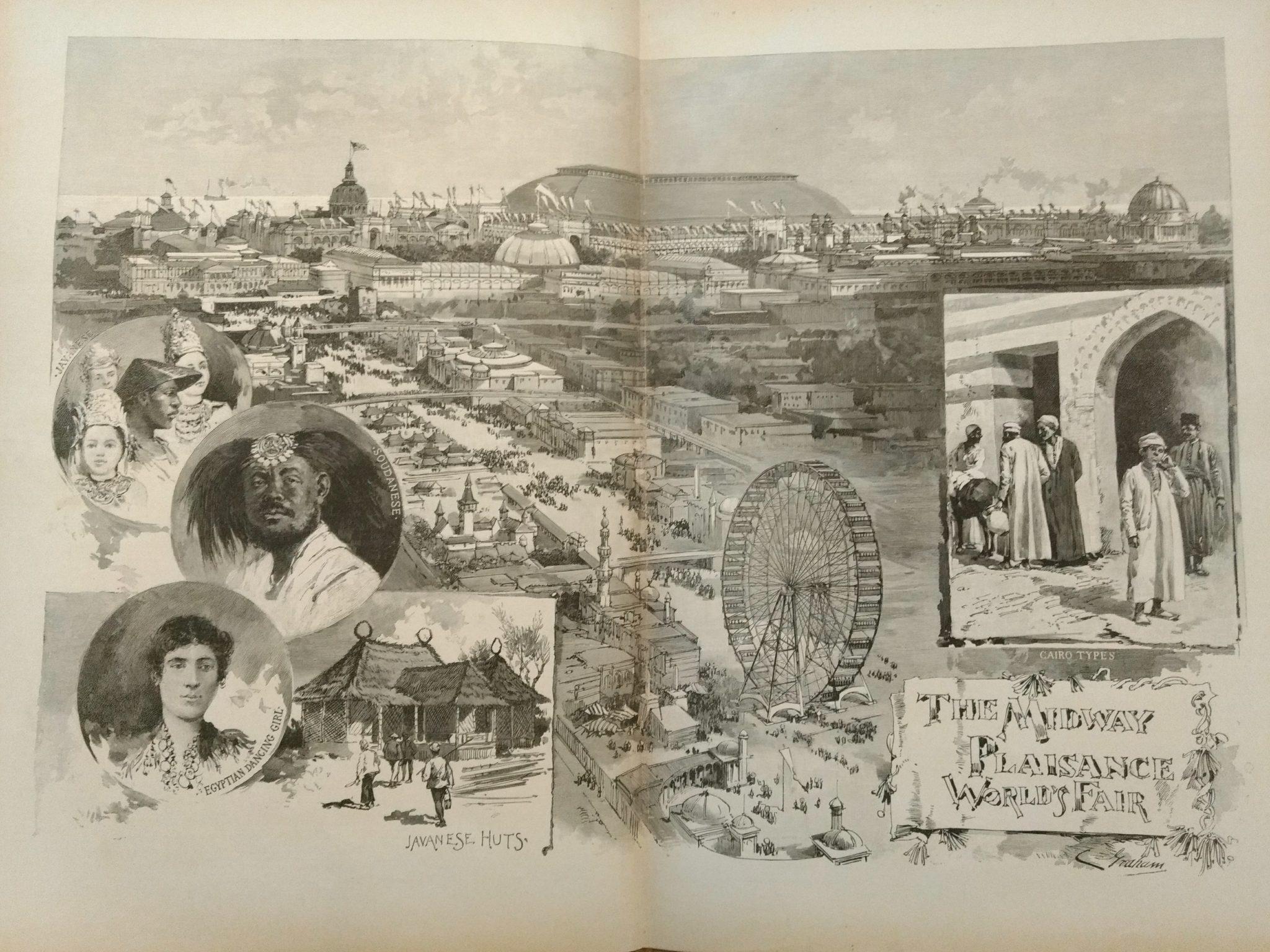

The first gamelan in the United States was at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, as part of what was called the Java Village. As the reference to Christopher Columbus in the event’s name suggests, the Exposition was overtly tied to colonialism. It provided an opportunity for the United States to promote its growing influence as an industrialized world power, and the inclusion of the Java Village certainly exoticized Javanese culture. As Henry Spiller says in his book Javaphilia: American Love Affairs with Javanese Music and Dance, “aspects of the performances of music and dance in the Java Village contributed to and became emblematic of a particular brand of exoticism associated with Java – an idyllic image of gentle, childlike creatures who spent their time crafting objects of exquisite beauty and mounting spectacular dramatic productions. Furthermore, Javanese performing arts became fixed as convenient indexes for this image of a gentle human nature devoted to a world of aesthetic beauty.”

It was through this event in the United States, and likewise at similar world’s fairs, that Western cultures became fascinated with aspects of Javanese culture, frequently through an exoticized lens. These expositions were critical in bringing the influence of Javanese gamelan into classical music of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Notably, French impressionist composer Claude Debussy attended the 1889 Paris Expo and heard Javanese gamelan for the first time. This experience went on to influence his music immensely, inspiring him to compose using similar scales as Javanese gamelan music, which can be heard especially in his piano piece, “Pagodes.” As the twentieth century progressed, more composers were inspired and influenced by gamelan to varying degrees, including Henry Cowell, Harry Partch, Olivier Messiaen, Béla Bartók, Maurice Ravel, and Colin McPhee. The Chicago Exposition also provided the space for the oldest known recordings of Javanese gamelan, thirty-four wax cylinders of the Java Village recorded by Benjamin Ives Gilman. A sample of these recordings can be heard on the Library of Congress website.

In contemporary music programs at universities and conservatories in the United States, two types of ensembles which are commonly offered as courses for students are West African drumming and Indonesian gamelan. The abundance of these ensembles is due to them being formed in the mid-twentieth century as part of growing ethnomusicology programs in certain colleges, reflecting the research interests of the professors at these institutions. Ethnomusicology, which is the study of music through fieldwork conducted by the researcher, including interviews, field recordings, and observation, was gaining a larger presence in the American university alongside what is often referred to as historical musicology, which studies music through research of books, newspapers, periodicals, and primary source materials. Ensembles such as gamelan were major contributions of ethnomusicology programs, helping to legitimize the field in American universities.

The first Indonesian performance program was established at UCLA in 1958 by ethnomusicologist Mantle Hood, who advocated for a hands-on approach to college music education in which students participated in ensembles to learn about the music through experience. As the twentieth century progressed, American college music programs wanted to align with growing diversity initiatives within universities as a whole, and introducing gamelan to their curricula seemed to be the perfect fit. However, many of these ensembles were incorporated into music programs with a Western classical music mindset still heavily in mind. For example, students taking a gamelan course could connect their experiences there with their music history courses which taught about Debussy and how gamelan influenced his music. Elizabeth A. Clendinning wrote in her book American Gamelan and the Ethnomusicological Imagination, “As the European-American artistic canons taught across the Western world were fractured and reassembled in more globally inclusive forms in the decades following World War II, it was gamelan – a versatile vocations of the world’s ‘other orchestra’ – that found itself at the heart of this self-consciously diversified new order.”

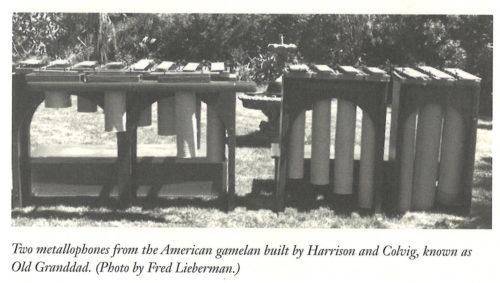

Amongst the teaching of gamelan in American universities, gamelan was playing an increasing role in the development of American New Music in the mid-twentieth century as well, finding a place amongst the instrument builders of New Music, notably Lou Harrison, Dennis Murphy, and Daniel Schmidt. These gamelan-like instruments were often built from scrap iron and aluminum. Lou Harrison and his partner William Colvig were pioneers in these constructions, building three instruments, the first of which called “An American Gamelan,” and eventually affectionately referred to as “Old Granddad.” The other two instruments ended up at San Jose State University and Mills. Lou Harrison and Daniel Schmidt met at the Center for World Music in Berkeley, California in 1975, the start of a series of collaborations in American gamelan.

Daniel Schmidt studied composition and Javanese music at the California Institute of the Arts, where he learned from the composers Ki Wasitodipura and Morton Subotnick. He eventually came to teach gamelan and instrument building at Mills College, an essential academic institution in the history of American experimental music, with figures such as Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich, Laurie Anderson, Anthony Braxton, Robert Ashley, David Behrman, Roscoe Mitchell, Joanna Newsom, Holly Herndon, and Luciano Berio passing through its doors in some capacity or another. Mills was founded in 1852, but began garnering a reputation as an innovator in music in the 1930s when John Cage and Henry Cowell taught in the dance department. In 1966, electronic composer Pauline Oliveros was the first director of the Mills Tape Music Center, eventually renamed the Center for Contemporary Music, leading into the 1970s when Schmidt would come onto the scene.

During his time at Mills, Daniel Schmidt built three gamelan sets, the Mills College Gamelan, the Berkeley Gamelan, and the Sonoma State Gamelan. He also composed music for his instruments, bringing together elements of Javanese gamelan and American minimalism, the latter of which was taking off at this time through his contemporaries Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and John Adams. Compositions like Schmidt’s and Lou Harrison’s came to define the specific style of American gamelan music.

Schmidt’s compositions were not available via recording for decades, despite the proliferation of gamelan records in the late twentieth century. In 2016, Recital put out the first album of Schmidt’s work, In My Arms, Many Flowers, which brings together recordings from Schmidt’s personal cassette collection spanning 1978 – 1982. On this record, Schmidt is working with the Berkeley Gamelan. The studio recording, “And the Darkest Hour is Just Before Dawn,” is a prime example of Schmidt’s melding of gamelan and New Music influences, his instrument combining with a sampler from Pauline Oliveros with a string quartet on it. In My Arms stands as an essential document of this prolific time period in New Music, and is an absolutely gorgeous record. Relaxing, engaging, creative, and complex.

We also have copies of the third Daniel Schmidt record, Cloud Shadows, which features him with the Mills Student Ensemble and the Gamelan Encinal. The compositions are more recent and the recordings were made in 2017 and 2019, reflecting experiences in Schmidt’s life such as his cancer treatment, creating homages to John Cage and Lou Harrison, and incorporating poetry and voice into his works.

Mills College stopped accepting new students last year, and no more degrees will be granted from the college next year. The college is now merging with Northeastern University to become a campus of the latter. This is a great change, perhaps loss, for experimental music, as much innovation has still been happening there and Schmidt is still on faculty. As that chapter in the history of American gamelan morphs into something new, we can still celebrate the contributions made by composers like Schmidt, dive further into and critique the deep, thorny, and fascinating history of Javanese influence in the United States, and bask in the beauty of gamelan music from Java, Bali, the Sundanese group of Indonesia, the United States, and anywhere where this musical tradition has made an impact.

Resources

Martin Buzacott, “Classically Curious: Debussy and the Paris Expo of 1889,” ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) (2019)

Elizabeth A. Clendinning, American Gamelan and the Ethnomusicological Imagination (2020)

Jennifer Lindsay, Javanese Gamelan: Traditional Orchestra of Indonesia (1992)

Marc Masters, “A Guide to the Extensive Musical Legacy of Mills College,” Bandcamp Daily (2021)

Leta E. Miller & Fredric Lieberman, Lou Harrison (2006)

Henry Spiller, Focus : Gamelan Music of Indonesia (2008)

Henry Spiller, Javaphilia: American Love Affairs with Javanese Music and Dance (2015)

Sumarsam, Javanese Gamelan and the West (2013)

In the Shop

Daniel Schmidt – Cloud Shadows (CD) (Bandcamp)

Daniel Schmidt – In My Arms, Many Flowers (CD) (Bandcamp)

More from Recital

Eric Anderson – The Crying Space (CD)

FPBJPC – Jubilee (LP)

Geoffrey Hendricks – Stones (LP)

Liv Landry, Sean McCann, & Eric Schmid – St. Francis (LP)

Mary Mazzacane – The Art of Mary Mazzacane (LP)

Molly McCann – Das Jahr (CD)

Sean McCann – Puck (LP)

Charlie Morrow – Chanter (CD)

Aki Onda – Nam June’s Spirit (LP)

Loren Rush – Dans le Sable (LP) (CD)

Eric Schmid – Dedicated to Dieter Roth (LP)

Adriano Spatola – Ionisation (LP)

V/A – Towards A Total Poetry (LP)

Also check the modern composition and international sections!

– Hannah Blanchette

July 24, 2022 | Blog