Sound, The Natural World, and the Work of Alvin Lucier

“I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice, and I am going to play it back into the room again and again, until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed.”

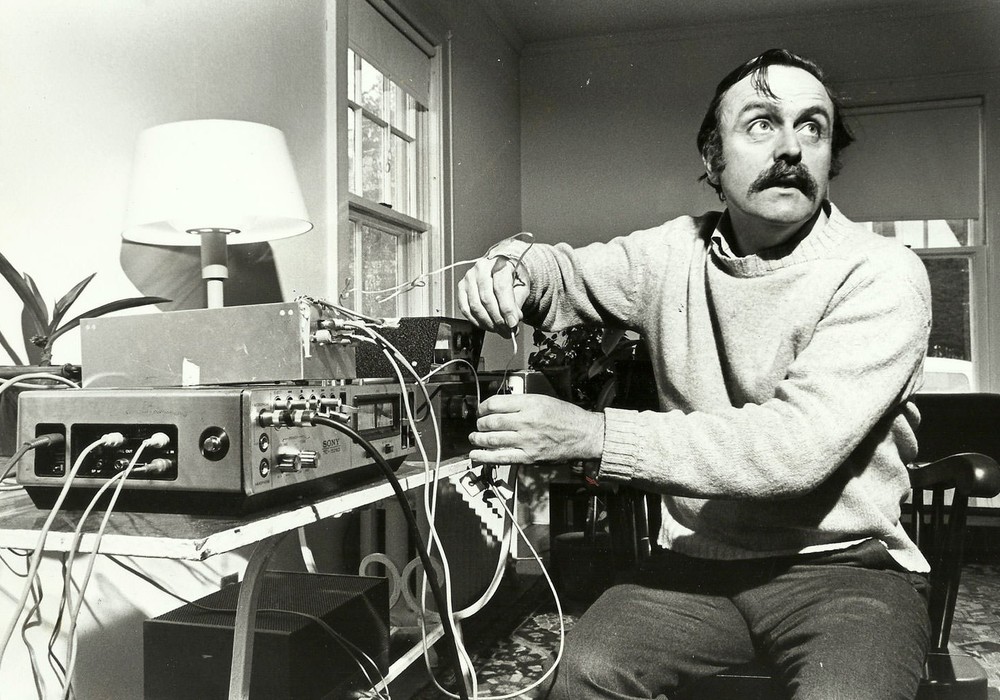

With this text spoken in Alvin Lucier’s 1969 work, I am Sitting in a Room, Lucier challenges preconceived notions of sound, speech, and space, a common thread throughout his work. Lucier passed away at the age of 90 on December 1, and this week we honor him by taking a look back on his life and work.

Alvin Lucier, c. 2014-15, Source

Lucier was born in 1931 in New Hampshire, growing up in a musical family. He would go on to study music theory and composition at Yale and Brandeis, studying under composers such as Aaron Copland and Lukas Foss during this time. Influenced by his teachers, Lucier initially composed in a neoclassical style, but soon became disillusioned with that style of composition. He told The New York Times in 1997, “I was literally exhausted by the neo-Classic style, and I had a couple of teachers that were at an impasse. They were getting bitter, and they were sort of losing their enthusiasm. And I was just at that age where I was ready for something new. But I didn’t know what to do.”

Lucier would discover “what to do” upon traveling to Rome on a Fulbright fellowship in the early 1960s. While there, Lucier attended performances by John Cage and David Tudor, and was introduced to the avant-garde works of composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, and Luigi Nono. For Lucier, there was no going back to neoclassical composition at that point, and he devoted his work to studying the relationship between sound and its environment from then on.

Lucier’s first foray into this study occurred while he was on faculty at Brandeis upon meeting physicist Edmond Dewan. Dewan had recently invented a brainwave control device, and Lucier collaborated with him on Music for Solo Performer (1965). Lucier attached electrodes to himself, which were connected to gongs, timpani, and snare and bass drums. Through this, the music was created via his own alpha brain waves. From the performer perspective, Lucier stated, “To release alpha, one has to attain a quasi-meditative state while at the same time monitoring its flow. One has to give up control to get it.”

Sonic Arts Union, Source

Soon after Music for Solo Performer, Lucier formed the Sonic Arts Union in 1966 with Robert Ashley, David Behrman, and Gordon Mumma. Along with Mary Ashley, Shigeko Kubota, Barbara Lloyd, and Mary Lucier, the collective would tour together and share equipment. Compositions by the entire group can be heard on their record Electric Sound from 1972.

Lucier contributed his piece, Vespers (1968) to this record. Vespers explores how animals, such as bats and dolphins, communicate through echolocation by emulating the process as humans. Lucier’s fascination and respect for the natural world permeates the process of composing this work.

In an interview with Walter Zimmerman for Desert Plants: Conversations with 23 American Musicians, Lucier talked about how when he discussed Vespers with people, they asked why he didn’t use recordings of the animals’ echolocation. In response, Lucier said, “That doesn’t interest me at all, the sound of bats. What interests me is the way bats operate…In imitating the natural, ah the way that the natural world works, you find out about it, and you also connect to it in a beautiful way. You don’t exploit it. I would feel that recording dolphins or bats or something as somehow exploiting their art. I would rather do what they do, on the level that we’re able to.”

Much of Lucier’s work emphasized relinquishing human control of natural occurrences. In 1977, Lucier composed Music On A Long Thin Wire, which challenged performers and audiences to resist the temptation to make music “interesting.” Lucier struggled with the same impulse while working on the piece, resisting (and sometimes failing to resist) the urge to adjust the wire after he set and tuned it. For Music On A Long Thin Wire, the intent is to passively perceive what the wire does through its own natural movements, not to manipulate it.

While Lucier acknowledged that many people received the work that way when it was installed at the Soundings show, he also lamented those who missed this concept. In a 1981 interview with Arthur Margolin for Perspectives of New Music, Lucier recalled, “Last year, I brought a class of students to Music On A Long Thin Wire, and they raced in and tried to make the wire do something. It was appalling. It doesn’t seem a tasteful way to approach anything – not just art, but life in general. It’s the egoistic, childish idea of look-what-I-can-do, whereas what is really beautiful about the piece is what the wire does. It has nothing to do with performers being virtuosi, or audiences having a good time by participation. Rather, you’re quiet and you pay attention.”

By listening to Lucier’s music and reading what he has written and spoken about sound, space, the natural world, and how to approach it, you strengthen your own ability to let go of control, be receptive to a musical experience, and remain open minded to the possibilities of sound.

Further Resources

I highly recommend this 2016 episode with Alvin Lucier on the podcast Son[i]a, in which he speaks generally on sound and space, while also in relation to his work. My personal favorite moment is his recollection of a time when he thought Pierre Boulez could have relinquished a bit of compositional control too.

The books and articles used to research this blog have a lot of amazing information of interest to fans of avant-garde and new music. The books are linked below to OhioLink pages where you can borrow them if you have an Ohio public library card. Articles and sites are directly linked.

Larry Austin and Douglas Kahn (editors), Source: Music of the Avant-Garde, 1966-1973 (2011)

*You can also go to the Main Library of Cincinnati’s Public Library and look at original issues of Source from 1967-1972.

Lars Gotrich, “Alvin Lucier, Inquisitive and Innovative Composer, Has Died at 90” NPR (2021)

Tom Johnson, The Voice of New Music: New York City 1972-1982: A Collection of Articles Originally Published in The Village Voice (1989)

Allan Kozinn, “Music Reconceived as Acoustical Sculpture” The New York Times (1997)

Alvin Lucier, Music 109: Notes on Experimental Music (2012)

Arthur Margolin, “Conversation with Alvin Lucier” Perspectives of New Music (1981)

Sonic Arts Union information site

Walter Zimmerman, Desert Plants: Conversations with 23 American Musicians (1976)

-Hannah Blanchette

December 12, 2021 | Blog