How Laurie Spiegel Expanded the Universe of Computer Music

In 2022, anyone with access to a computer has the opportunity to create computer music. I learned how to use GarageBand at a camp as a teenager, and later was able to install the software for a low price on my own computer after the camp concluded. The use of computers in the creation and production of music is often taken for granted today, as they became as ubiquitous in music as they did in other aspects of daily life. When Laurie Spiegel began innovating computer music in the mid-seventies, computers equipped to write music were not as accessible, instead restricted to a research setting and shared amongst multiple composers. The byproduct of her initial work on computer music, her pioneering debut album from 1980, The Expanding Universe, was reissued and expanded to three LPs in 2019. We recently stocked this record in the shop and look back this week on Laurie Spiegel’s contributions to the development of computer music.

In 2022, anyone with access to a computer has the opportunity to create computer music. I learned how to use GarageBand at a camp as a teenager, and later was able to install the software for a low price on my own computer after the camp concluded. The use of computers in the creation and production of music is often taken for granted today, as they became as ubiquitous in music as they did in other aspects of daily life. When Laurie Spiegel began innovating computer music in the mid-seventies, computers equipped to write music were not as accessible, instead restricted to a research setting and shared amongst multiple composers. The byproduct of her initial work on computer music, her pioneering debut album from 1980, The Expanding Universe, was reissued and expanded to three LPs in 2019. We recently stocked this record in the shop and look back this week on Laurie Spiegel’s contributions to the development of computer music.

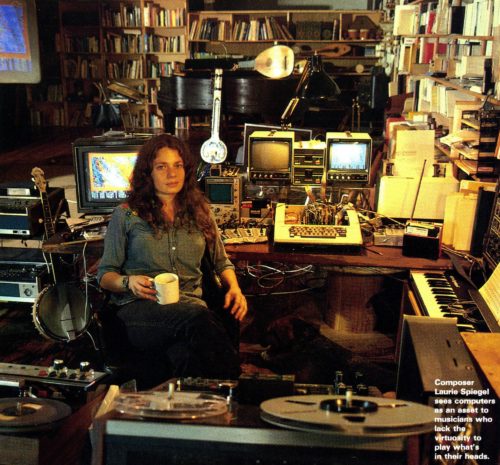

Laurie Spiegel’s musical beginnings were somewhat diametrically opposed to the futuristic music she’d eventually make in the seventies. As a teenager, Spiegel learned how to play guitar, mandolin, and banjo, possessing an interest in blues and folk music, which also inspired the three-part work on The Expanding Universe (expanded version) titled “Appalachian Grove.” Her love of these instruments continued into her college days when she studied abroad at Oxford University. While there studying social science, she also took composition and guitar lessons with John W. Durante. When she returned to the States, this interest in music continued and she decided to get a Masters in Composition at Juilliard. While in New York in the late sixties, she studied with Michael Czajkowski, who brought her to electronic composer Morton Subotnick’s studio, where she became familiar with the Buchla synthesizer.

Her early experiences with analog synthesizers caused Spiegel to notice the conveniences of composing electronic music. She stated, “You were making the sounds yourself, as opposed to writing them down on a score and then hoping you could persuade a conductor and an orchestra to turn them into sound. You could immediately hear the realization of your ideas.” One of her early analog compositions from 1972, “Sediment” appeared on the fourth volume of the Anthology of Noise and Electronic Music series. Although Spiegel enjoyed working with analog synthesizers, the challenges that came with composing in a shared studio where she couldn’t save her daily work were a downside. Furthermore, she was interested in pathways that would allow her to compose electronic music in a more improvisatory way. Spiegel began to explore methods of composition that solved this challenges when she started working at Bell Labs in the mid-seventies.

Her early experiences with analog synthesizers caused Spiegel to notice the conveniences of composing electronic music. She stated, “You were making the sounds yourself, as opposed to writing them down on a score and then hoping you could persuade a conductor and an orchestra to turn them into sound. You could immediately hear the realization of your ideas.” One of her early analog compositions from 1972, “Sediment” appeared on the fourth volume of the Anthology of Noise and Electronic Music series. Although Spiegel enjoyed working with analog synthesizers, the challenges that came with composing in a shared studio where she couldn’t save her daily work were a downside. Furthermore, she was interested in pathways that would allow her to compose electronic music in a more improvisatory way. Spiegel began to explore methods of composition that solved this challenges when she started working at Bell Labs in the mid-seventies.

Bell System, who monopolized telecommunications in the seventies, also had their research division, Bell Labs, where research was conducted in telecommunications, human cognition, and the relationship between arts and technology. Spiegel was brought to Bell Labs by Max Mathews, one of the inventors of the GROOVE (Generated Realtime Operations On Voltage-controlled Equipment) system. She learned programming on the system and began a position as a Resident Visitor, for which she was paid to write music for various situations, like for tech showcases. Although the work she did as Resident Visitor was for commercial purposes, she also had access to cutting-edge compositional technology that she would not be able to find anywhere else, along with time to experiment with it.

The GROOVE system was an interconnected system of microcomputers that were also connected to synthesizers, allowing the computer to compose music in real-time. Spiegel has talked about how GROOVE freed up so many possibilities for her as a composer. “I was an improviser, I liked to make up stuff in direct contact with the sounds. Because it offloaded the actual generation of sound to the synths, GROOVE was freed up to be a control mechanism. You could program– visibly write what we called ‘transfer functions’– and you could hear the results straight away. And because the system was digital, you could store it all on magnetic tape, which meant you could pick up right where you left off the next day.”

GROOVE would accompany Laurie Spiegel as she composed two of her most iconic works in the late-seventies. The first of which was created at the request of NASA. In 1977, Carl Sagan organized a project for the Voyager space probes called the Golden Record or The Sounds of Earth, a record to be placed on both Voyager probes that compiled information and music to be shared with extraterrestrial life if contact is ever made. The record included music from Bach to Chuck Berry, animal sounds, greetings in various languages, and EEG brainwaves. Spiegel was asked to create the opening track, a computer realization of seventeenth-century German astronomer Johannes Kepler’s composition, Harmonices Mundi. Kepler used the Pythagorean theorem to attempt to realize the “music of the spheres” based on planetary orbits. In the seventeenth century, the technology did not yet exist to turn his math into music. As Spiegel said, “Kepler had written down his instructions [in 1619], but it had not been possible to actually turn it into sound at that time. But now we had the technology. So I programmed the astronomical data into the computer, told it how to play it, and it just ran.”

Not only could GROOVE realize Kepler’s ideas, it helped bring about Spiegel’s own on her debut album, The Expanding Universe. Although GROOVE couldn’t achieve the timbral color palette that one could get through a Buchla, she could experiment with precise modes of composition one could only achieve through a computer. She discussed how this manifested on the track “The Orient Express” (which appears on the expanded version of the record): “If you listen to ‘The Orient Express,’ the melodic line and motivic content, it evolves throughout. It doesn’t fall into repeating loops, it doesn’t fall into drones, it keeps evolving. Rhythmically it contains the illusion of perpetual acceleration. It keeps on getting faster and faster, but it never actually gets faster.”

The cover of The Expanding Universe is as fascinating as the music itself, the liner notes adorning the cover and written in interview style, with Spiegel as both the interviewer and interviewee. She asks herself standard questions as a slightly condescending, confused interviewer, which she also responds to with clear detail. The album art anticipates how others would consider computer music and her compositions in general, a shrewd commentary on the music promotion process and on music reception broadly.

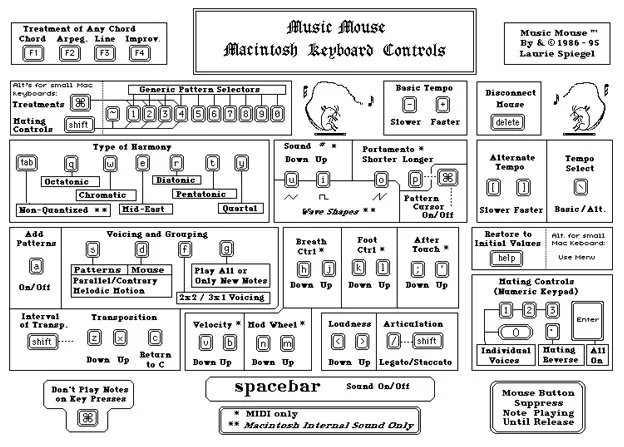

Inspired by GROOVE, Spiegel also worked on a system called VAMPIRE (“Video and Music Program for Interactive Real Time Exploration and Experimentation”), which would tie together visual and auditory output during the compositional process. However, this development was cut short when GROOVE was shut down in 1978. Without GROOVE, Spiegel began work on creating a new computer software for composition. With the rise of personal computers in the eighties, Spiegel was able to create “Music Mouse – An Intelligent Instrument” for Mac, Atari, and Amiga operating systems. This software composed sound through moving your mouse, and was the basis of her 1991 album, Unseen Worlds. The difference in equipment and compositional process between The Expanding Universe and Unseen Worlds outlines the development of computers in general and how computer music gradually moved from labs to the home.

Just as Spiegel was always right in step with computer music innovations, if not a little ahead, she was also ahead of her time in her written prose as well. Spiegel’s written word often eerily spoke on topics in music that were not yet full fledged issues or phenomena, such predicting the circulation of music via the Internet in “Music and Media,” written for Ear Magazine East in 1981, music and tech nostalgia and revivals in “On the Nostalgia Boom,” published in The New York Times in 1990, and the use of outdated technology in “That was Then ⇔ This is Now” in a 1995 issue of Computer Music Journal.

During the seventies, Spiegel was an integral member of the downtown New York New Music scene of the decade, which reacted against the confines of the classical music institutions of uptown New York. Along with Spiegel, figures such as Laurie Anderson, Robert Ashley, Phil Niblock, and Arthur Russell drove this scene, bringing together music and performance art in spaces such as The Kitchen, and circulating through record labels like Lovely Music and Chatham Square. Whether she was alone in a computer lab or commiserating with the New Music artists of the day, Laurie Spiegel was and has continued to be an essential figure in innovating computer music as the technology itself developed. The title, “The Expanding Universe” is immensely appropriate for her first record, as not only is her music currently hurtling through space outside the boundary of our solar system, but her compositions also expanded how we even conceived of writing music.

Resources

Laurie Spiegel’s website [definitely check this out, she has so much information here]

Tobias Fischer, “Interview with Laurie Spiegel,” Tokafi (c. 2012)

“Laurie Spiegel,” NAMM (2017)

Justin Patrick Moore, “The Bell Sound 3: Grooving with Laurie Spiegel,” Sothis Medias (2020)

Frank J. Oteri, “Laurie Spiegel: Grassroots Technologist,” New Music Box (2014)

Simon Reynolds, “Resident Visitor: Laurie Spiegel’s Machine Music,” Pitchfork (2012)

Alex Ross, “The Interstellar Contact,” The New Yorker (2014)

“Voyager – The Golden Record,” NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Seth Colter Walls, “An Electronic-Music Classic Reborn,” The New Yorker (2012)

Kevin Warwick, “Four Electronic Artists Reflect on the Influence of Composer Laurie Spiegel,” Bandcamp Daily (2018)

Products

Laurie Spiegel – The Expanding Universe

Items from Lovely Music

More in Modern Composition / Musique Concrète / Electronic

– Hannah Blanchette

May 15, 2022 | Blog