Decades of Dreamy Electronic Organ from Mamman Sani

Sahel Sounds record label and blog founder Christopher Kirkley blew the dust off a cassette he found in an archive at Niger’s national museum. By the end of his initial listen, Kirkley was captivated by the oft-described “dreamy” sounds of the electronic musician Mamman Sani Abdoulaye. While Sani’s music seemed like a long-forgotten treasure to Kirkley, Sani remained a well-known figure amongst Niger’s avant-garde throughout the decades from when that tape was recorded, as well as his music existing in the minds of the population through his compositions for radio and television. In the past decade, his music has gathered a following outside the boundaries of Niger, spurred on by a Sahel Sounds reissue of this first cassette.

Sahel Sounds record label and blog founder Christopher Kirkley blew the dust off a cassette he found in an archive at Niger’s national museum. By the end of his initial listen, Kirkley was captivated by the oft-described “dreamy” sounds of the electronic musician Mamman Sani Abdoulaye. While Sani’s music seemed like a long-forgotten treasure to Kirkley, Sani remained a well-known figure amongst Niger’s avant-garde throughout the decades from when that tape was recorded, as well as his music existing in the minds of the population through his compositions for radio and television. In the past decade, his music has gathered a following outside the boundaries of Niger, spurred on by a Sahel Sounds reissue of this first cassette.

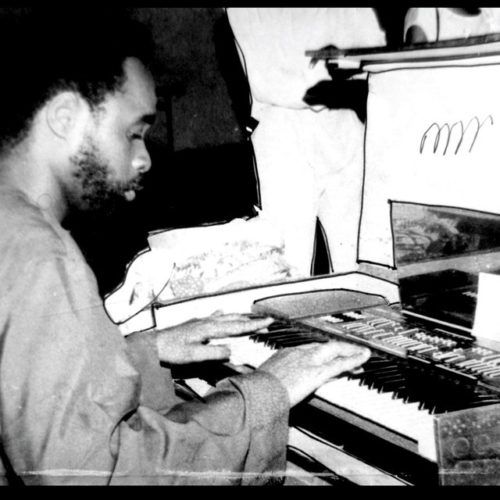

Mamman Sani was born in 1952 in Accra, the capital of Ghana, moving to Niger a few years later. Sani began learning music in his teenage years, starting out with a borrowed harmonica. He used to play the French hits of the day on the instrument, and eventually began to learn guitar as well, all while listening to artists such as James Brown, Otis Redding, and Percy Sledge. However, he wouldn’t be introduced to his instrument of choice until 1974. Sani first began working as a teacher before taking on a position as a functionary for UNESCO. His job brought him to Europe and Japan, and it was while on these travels that he first encountered the Italian “Orla” organ, owned by a delegate from Rwanda. It was a “love at first sight” experience, and Sani purchased the organ directly from the delegate.

The Orla organ had impressive functionality, coming with pre-programmed orchestral sounds and basic drum machine capabilities. With the organ, Sani began developing his unique sound, which combined elements of Nigerien folk music and minimal electronic music practices. His first and only album was recorded in 1978 as part of a cassette project organized by the Minister of Culture to compile contemporary music in Niger. However, the project didn’t really get off the ground and only about 100 tapes of Sani’s album were produced and released in 1981. Sani still only knows the whereabouts of two copies, the one in the national museum’s archive and his own.

Although only two known copies of this initial cassette exist, thousands of people now have reissued and remastered copies on LP, CD, and cassette through both Sahel Sounds and Mississippi Records as La Musique Electronique du Niger beginning in 2013. Immediately after Christopher Kirkley listened to Sani’s album, he talked with the archive director about getting contact information for Mamman Sani. Sometimes, it can take months or years for people like Kirkley or Awesome Tapes From Africa’s Brian Shimkovitz to get in touch with the artists of tapes they find. And sometimes they are never able to find them at all. In this case, Kirkley was able to make contact immediately, chatting with Sani on the phone that day and arranging to meet the following day.

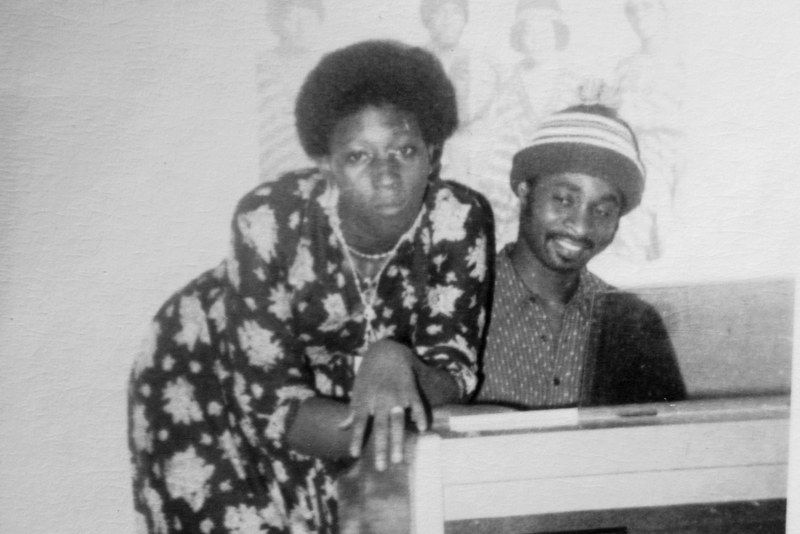

Through meeting with Sani, Kirkley was able to learn more about Sani’s music and career. In particular, they discussed a song of his, “Salamatu.” Sani had written the track for his girlfriend. Kirkley recalled, “He stopped as he came across her photo, how he once lay with his head in her lap, and tears came to his eyes. When she asked him why he was crying, he answered: ‘Because I’ve never been so happy as I am in this moment.’” The piece, which was included on his first record, captures this wistful feeling of love with a yearning melody soaring over an insistent, repeating bass line. “Salamatu” can even be seen performed with text sung by Dr. Mammane Garba in this short music video clip below.

Another track on this first record, “Bodo,” aptly shows how Sani brought together inspiration from folk music and electronic compositional approaches. “Bodo” draws from musical techniques of the Wodaabe tribe, whose singing style is polyphonic (multiple musical lines emerging and intertwining). Each person sings their own improvised melody, which gradually develops and changes as the song progresses. Sani emulates this process on “Bodo,” electronically rendered with his organ as he continually introduces new melodic lines and weaves them together over a consistent drum beat.

Although Mamman Sani’s first album didn’t make a big splash upon release in 1981, his career didn’t end there. Sani worked for decades as a composer and performer for television and radio, writing background and interlude music for programs, AKA library music (a genre discussed on the blog a couple months ago). As is often the case with library music, most people in Niger knew his music, but didn’t know they knew it, the enigmatic figure behind the everyday media music of Nigeriens. Sani himself would even appear on television for a brief period with his show, Mamman Sani et son Orgue Électronique.

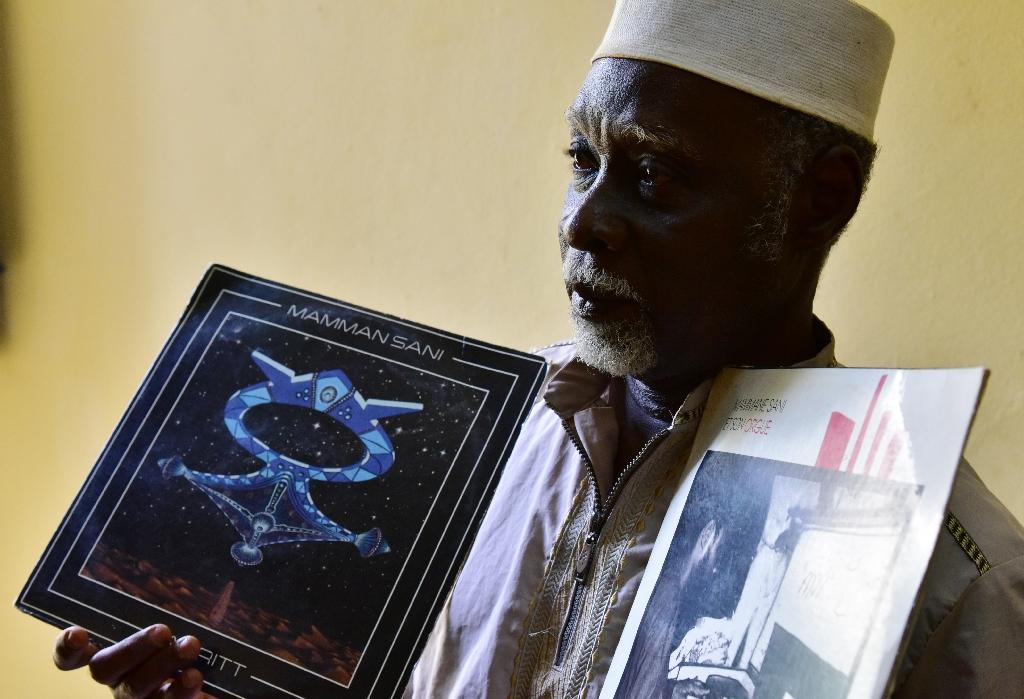

Throughout this period, Sani continued to record solo material as well. His recordings from 1985 through 1988 were first released in 2015 as the album Taaritt. Recorded in both Niger and France, Sani calls upon multiple electronic instruments for this record, using polyphonic analog synthesizers and drum machines such as the Crumar Bit 99, RCA Victor 70, Yamaha RX5, and Roland TR-505. This album leans more cosmic in its sound, tracks such as “Ya Bismillah” and “Dangay Kotyo” containing spacey background synths, chill beats, and a lively melody that still draws from folk ballads. Some even describe Sani’s work from this period as Afrofuturist.

In 2015, some unheard gems of Mamman Sani’s older work were released as Unreleased Tapes 1981-1984, which compiled extra tracks Sani recorded while he worked on his first album, which he was saving for a second record. Unreleased had a limited run, as did a cassette released in 2013 of some of Sani’s more recent recording sessions from the 2000s, titled Mamman Sani And The Workstation.

Mamman Sani is still an active musician to this day, performing live and splitting time between his home in Niger’s capital, Niamey and his recording studio in Ghana where he is working on many albums. When Sahel Sounds was working on the first reissue of La Musique Electronique du Niger in 2013, one of Sani’s friends said, “He’s been waiting over 30 years. It’s about time.” Almost a decade later from that moment, he now has a captive audience from around the world waiting with bated breath for whatever he has in store.

We recently restocked the LP remaster of La Musique Electronique du Niger and we also have Taaritt in stock. Plus, we have many other titles from Sahel Sounds and related record labels such as Mississippi Records and Awesome Tapes From Africa. Check out the list below for these and more recommendations of electronic music from Africa and music of multiple genres from Niger!

In the Shop

Mamman Sani – La Musique Electronique Du Niger – $20 (Bandcamp)

Mamman Sani – Taaritt – $20 (Bandcamp)

More from Sahel Sounds

Amanar de Kidal – Tumastin – $18

El Wali – Tiris – $21

Hama – Houmeissa – $24 (Recommended by Sani!)

Luka Productions – Falaw – $21 (Recommended by Sani!)

Troupe Ecole Tudu – Oyiwane – $21

Wau Wau Collectif – Yaral Sa Doom – $19

V/A – Music For Saharan WhatsApp – $20

V/A – Nouakchott Wedding Songs – $17

More Electronic Music from Africa

Ata Kak – Obaa Sima – $20

Francis Bebey – African Electronic Music 1975-1982 – $27

DJ Black Low – Uwami – $18

DJ Katapila – Trotro – $19

Teno Afrika – Amapiano Selections – $19

V/A – Borga Revolution! Ghanaian Music In The Digital Age, 1983-1992 (Volume 1) – $29

For even more great finds, take a look at our international, modern composition/musique concrète/electronic, and techno/house/electronic sections!

Resources

Maria Barrios, “Mamman Sani Abdoulaye Took Nigerien Music Into the Future,” Bandcamp Daily

Patrick Fort, “Mamman Sani’s Electric Sound Finally Travels Beyond Niger,” Yahoo News (2016)

Christopher Kirkley, “Mammane and His Electronic Organ,” Sahel Sounds (2013)

“Mamman Sani” artist page, Sahel Sounds

“Mamman Sani Abdoulaye :: Kok Kok Kok,” Aquarium Drunkard (2018)

– Hannah Blanchette

August 19, 2022 | Blog