Like Psychotropic Events: The Immersive Multimedia Presentations of Intersystems

The drive to make immersive multimedia experiences seems to be more mainstream than ever in contemporary culture. From 3-D movies to VR headsets, the sensation of completely transforming the setting around you continues to permeate technological advancements, some with ominous implications. For many decades now, artists and engineers have been combining cutting-edge technology with artistic endeavors to create immersive sensory experiences. One of these groups was Intersystems, a multimedia group from the late 1960s who combined avant-garde modular synthesis, poetry, light and electrokinetic sculptures, and large-scale installations to build what they called, “presentations.” As music critic Simon Reynolds points out, Intersystems was part of a small trend of North American psychedelic bands in the 1960s and 70s who incorporated electronics into their music to a greater degree than others on the continent, being more in-line with the psychedelic, prog, and krautrock coming out of Europe at the time.

Intersystems began in Toronto in 1967 when three of the four members, Michael Hayden, John Mills-Cockell, and Blake Parker met in a brand new electronic music class in the basement of the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. Hayden recalled the band’s genesis as: “The original inspiration for the group was to get me out of the hot water I had found myself in by declaring I could make an environmental installation that would emulate the experiences of a psychotropic event.” Soon joined by architecture and structural engineering student Dik Zander to create the light sculptures, Intersystems developed with Hayden working on installations, Mills-Cockell composing music, and Parker contributing spoken and written poetry to the project, each member twenty-fours-old and just getting their starts in their chosen fields.

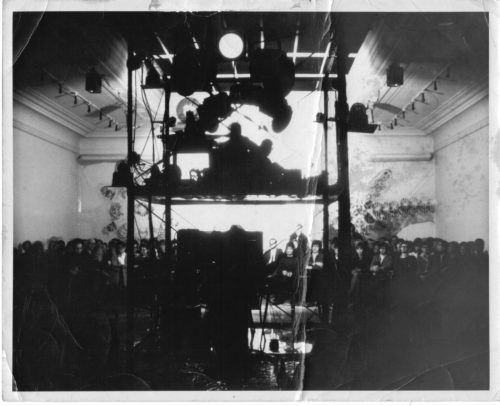

They were called upon to create their first “presentation” for the University of Toronto’s Perception 67 event. The event included a series of discussions on LSD and was highly attended, with numbers in the thousands (and with many turned away). Prominent figures came to Perception 67, including Allen Ginsburg, The Fugs, and via a video-recorded lecture, Timothy Leary (a plan B for him being stopped at the Canadian border). Without a doubt, Intersystems’ installation, Mind Excursion, was one of the highlights of the event. Simon Reynolds referred to it as “a psychedelic-era update of the Philips Pavilion,” which I think is spot-on.

The Philips Pavilion was an exhibit at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, put together by the Philips Electronic Company to demonstrate their recent technological advancements. Interior designer of the pavilion, Le Corbusier, said of the project, “I will not make a pavilion for you but an Electronic Poem and a vessel containing the poem; light, color image, rhythm and sound joined together in an organic synthesis.” The exterior was designed by architect and sound artist, Iannis Xenakis and musique concrète composer Edgard Varese was tasked with creating the sound environment for the space, titled Poème électronique. The result was a combination of architecture, electronics, sound and visual design, and musique concrète composition, the first of its kind.

Within eighteen months of Mind Excursion, Intersystems was able to have their own space akin to the Philips Pavilion, called the Mind Excursion Center. Located in Montreal, the center consisted of ten rooms, each with a unique, immersive sensory experience that played with all five senses. Mills-Cockell described it: “One would be all carpet, another would be totally pitch-black except for explosions of light. There was a water room, a chocolate room and a room that was all mirrorized. Each room had a different soundtrack. And then Blake recited this amazing futuristic soap opera poem – about the romance between two kids called Gordy and René – that tracked the action and the nature of each room.”

All three of Intersystems’ initial albums were recorded during those eighteen months as well, released over the course of two years: Number One Intersystems (1967), Peachy (1967), and Free Psychedelic Poster Inside (1968). Mills-Cockell was very inspired by chance procedures, such as I Ching, Dadaism, and beat poet William Burroughs’ cut-ups, all influences which found their ways onto the Intersystems records.

The first album, Number One Intersystems, was recorded before the band had access to a synthesizer, so the ingenious group built their own instruments. One notable instrument was called the Coffin. Mills-Cockell said, “It was this five-footlong board with strings strung along that you could pluck and hit. There was a box lined with purple satin fabric and the board sat on that. Underneath the purple fabric were concealed switches that allowed us to switch the sound between different pickups along the board and out to different speakers in the hall where we were playing.”

Released the same year, the follow-up Peachy was the first record Mills-Cockell was able to use a Moog on. He purchased the modular synthesizer from Bob Moog himself, who Mills-Cockell was visiting periodically in Trumansburg, New York. Peachy is the best example of Mills-Cockell’s influences distilled in one place. His process involved a combination of improvisation, musique concrète tape techniques, and standard composed music. With his tapes of the synthesizer, Mill-Cockell cut the tape and rearranged the order according to chance procedures.

The final record (until last year), Free Psychedelic Poster Inside, was a bit more traditional than its predecessors, mainly because each track on the album followed one compositional process, such as one improvisational track, one composed track, etc, unlike Peachy which brought together multiple techniques for one piece. The cheekiest part of Free Psychedelic Poster Inside was that there was, in fact, no free psychedelic poster inside.

Intersystems continued constructing installations around North America, from Vancouver to Washington DC, until early 1969, their final project titled Network II. Going forward, the Intersystems members became occupied by other projects and the group faded, Mills-Cockell going on to form the psych band Syrinx.

Intersystems’ short lifespan aligns with the characteristics Simon Reynolds outlines in his definition of what he thinks of as “synthedelia.” These psychedelic bands with heavy electronics from North America in the 1960s and 70s, such as Fifty Foot Hose, Silver Apples, and The United States of America, used abstract electronics extensively, had connections with the avant-garde, and would only release one or two records before disbanding. None of these groups were able to achieve the longevity of European contemporaries like Tangerine Dream, Heldon, or Can. Reynolds believes part of why these bands didn’t take off in the same way is the American rock’s more roots-based approach going into the 1970s, drawing upon folk and country more than electronics. Although, as Mills-Cockell said of Intersystems, “What we were doing was folk music. Blake’s poems are everyday stories and the sound is found art. We didn’t find it in junkyards, but we were always going through electronic stores selling clear-out circuitry. We were banging on instruments that we could barely keep in tune, or even wanted to.”

The innovations of Intersystems remained fairly dormant for decades, until the Italian label Alga Marghen reissued their albums as an extensive box set in 2015 (one copy available from us). All three LPs included, along with a 132-page book detailing the band’s history and a 110-page book including art and texts from the band. Then in 2021, Intersystems rose from their dormancy as well, releasing their first record since 1968, titled #IV. Blake Parker has since passed away, and current members Mills-Cockell and Michael Hayden electronically rendered Parker’s poetry on the record, combining his text with Mills-Cockell’s signature Moog sound. We recently stocked #IV on both LP and 2xCD from Suction Records. Although we can’t still visit immersive, warehouse-size installations from Intersystems (at least for now), grab a pair of noise-canceling headphones, close your eyes, and bring Intersystems home with you to create your own sensory experience.

The innovations of Intersystems remained fairly dormant for decades, until the Italian label Alga Marghen reissued their albums as an extensive box set in 2015 (one copy available from us). All three LPs included, along with a 132-page book detailing the band’s history and a 110-page book including art and texts from the band. Then in 2021, Intersystems rose from their dormancy as well, releasing their first record since 1968, titled #IV. Blake Parker has since passed away, and current members Mills-Cockell and Michael Hayden electronically rendered Parker’s poetry on the record, combining his text with Mills-Cockell’s signature Moog sound. We recently stocked #IV on both LP and 2xCD from Suction Records. Although we can’t still visit immersive, warehouse-size installations from Intersystems (at least for now), grab a pair of noise-canceling headphones, close your eyes, and bring Intersystems home with you to create your own sensory experience.

In the Shop

From Intersystems:

Intersystems – #IV, LP & CD

Intersystems – S/T

Related Items

The I Ching or Book of Changes

The United States Of America – S/T

Edgar Varese – Music Of Edgar Varese Vol. 2

Xenakis / Berio / Maderna / Kagel – Orient-Occident / Momenti – Omaggio A Joyce / Continuo / Transition 1

If you’re interested in Intersystems, also browse other titles from Suction Records, and the Art Rock/Krautrock/Prog/Psych and Modern Composition/Musique Concrete/Electronic sections!

Resources

Thom Holmes, “On the Road: Early Live Moog Modular Artists,” Moog Foundation (2016)

“Intersystems,” John Mills-Cockell Retrospective

“Intersystems: Intersystems,” PopMatters (2016)

“An Interview With John Mills-Cockell (Syrinx / Intersystems),” from Electronic Voyager, Synthtopia (2016)

Jesse Locke, “The Astral Excursions of John Mills-Cockell,” MusicWorks (2017)

Oscar Lopez, “AD Classics: Expo ’58 + Philips Pavilion / Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis,” ArchDaily (2011)

Simon Reynolds, “Synthedelia: Psychedelic Electronic Music in the 1960s,” Red Bull Music Academy (2018)

Andrew Timar, “Intersystems. Intersystems.,” MusicWorks (2016)

– Hannah Blanchette

August 12, 2022 | Blog